Does Data Lie?

By Paul Hogendoorn

Does data lie, or does it always reveal the truth? It’s an interesting question, at an extremely interesting time in world history. Readers of this column are likely to recall my oft-shared opinion that “context matters,” and that the narrative is as important to collect and consider as the empirical data. This has never been as important as it is now, with all the data collected, analysed and shared about COVID-19.

Data may be empirical and unbiased in and of itself, but the collection and analysis applied to it are not. For this, we have to understand confirmation bias – a human condition that we all have to one degree or another. People tend to filter out messages they don’t agree with and hold firmly to those they do, continually reinforcing what it is they already believe. Once an opinion or a bias has been established, it is very hard to have an outside influence change it. The filtering process is often applied to data analysis by selecting only specific subsets of the data, and tailoring the analysis to arrive at a desired conclusion. Taken out of context, and with a specific intent in mind, data can be used to lead to a desired conclusion, leveraging the implied credibility and “truth” of data.

Regarding intent, people analyze data with an inherent confirmation bias built in. Even the “scientific method” begins with a hypothesis – a human assumption of what they suspect is correct, from which a series of tests is then designed to prove or disprove that assumption. Scientists, by and large, are extremely disciplined in their approach, and remain open to either possibility, genuinely driven with the pure intention of new discovery. The same is not true for anyone trying to influence the opinion of the masses on any topic – social, political, or now most notably, COVID-19. There is a steady stream of headlines each day revealing new “facts” and implied truths based on data, but the data is seldom presented in full and accurate context – because it no longer needs to be; the headlines and factoids are already feeding into a firmly entrenched confirmation bias

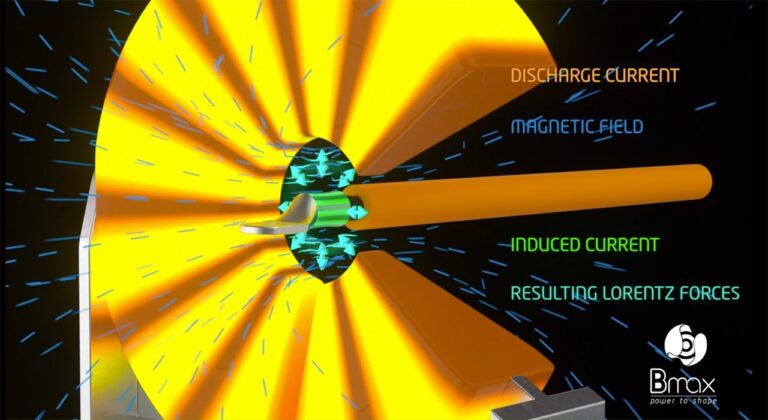

Some may hold that to perform true non-biased, empirical analysis, the human influence needs to be removed, and that perhaps this could be done by employing artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning (ML) technologies. The problem here though, is that these technologies are already being used widely in society for exactly the opposite reason – to influence our behaviour by first learning it, then finding ways to influence it. Social media feeds AI systems that learn your behaviour, your opinions and predict your inclinations, then delivers you a steady diet of small messages designed to influence your next purchasing decision, or your next vote. Before the internet and social media, these things happened broadly, through newspapers, TV news and radio stations. Our confirmation bias was fed by our choice of what paper we subscribed to, and which news stations we watched or listened to. Regulations and oversight were in place to protect society. With social media as the I/O device into so many of our lives, and the power of AI and ML technologies as the processing engine, empirical data can be collected, analyzed, and reports engineered with even more power and impact, and with the perception of scientific neutrality – with less oversight, accountability, or protection for society.

Data is useful for many things, and data-driven decisions are valuable. But context and intent are key. In manufacturing companies, the purchasing group uses data as empirical proof they have lowered costs of tooling. Engineering however, uses data to show that the new tooling has a significantly lower meantime between failure. The quality department uses data to prove that scrap rates have gone up and that warranty costs will rise for an extended period of time. All of them use data, but most often, the purchasing department wins the day because its data and metrics are easiest to understand, resulting in a strong confirmation bias that needs to be overcome. The near-term effect weighs heavier than the long-term cost. Purchasing gets the nod because they achieve their immediate-term goals while the effects only show up in financial statements indirectly sometime next year, or four years from now. The other voices have a long, hard uphill climb to influence the company to the eventual proper decision later, costing the company exponentially more than they may have saved with the short-term decision.

And so it is with COVID. Politicians’ approval ratings are at an all time high – whether right wing or left wing, and the six-o’clock news has not had this many regular, engaged viewers tuning in daily in a long while. It’s an uphill battle for those with an opposing view.

Data doesn’t lie, but that doesn’t mean data is always telling the truth. For that, we have to be willing to dig deeper, understand context, and when necessary, examine intent. Technologies may provide us with ever-increasing amounts of data, and increasingly powerful analysis tools, but there are no shortcuts or opt-outs. It’s still up to us personally to really understand what the data is telling us.