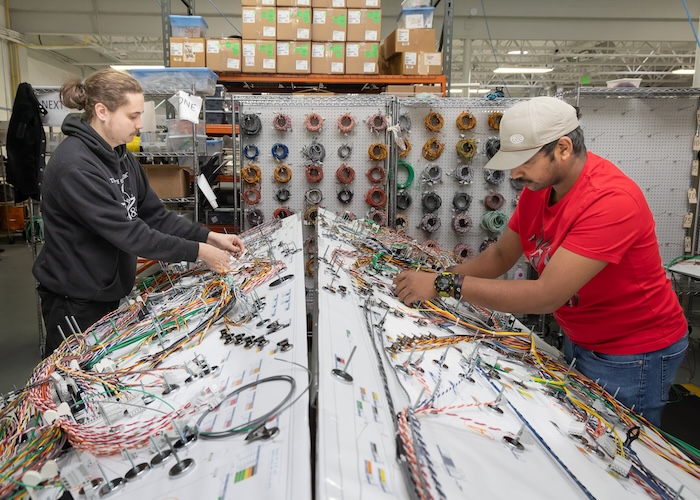

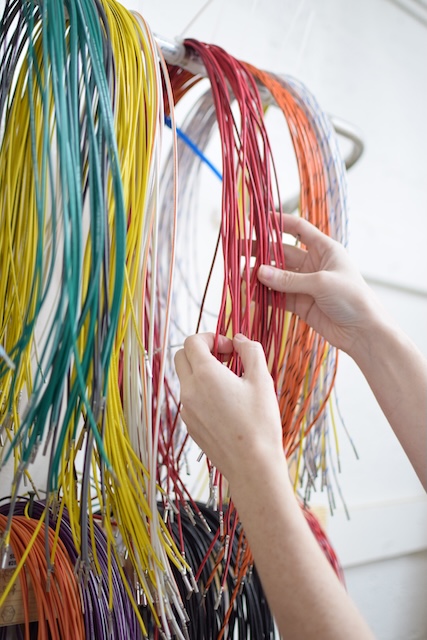

The word “manufacture” is said to come from two words: “manu”, which comes from classical Latin word for “hand”, and “facture”, which is the Middle French term for “making”. The first recorded usage of the word “manufacture” was in the middle of the 16h century and referred to making something by hand.

This first reason I love manufacturing is very personal: as the above definition states, its very tactile and “kinesthetic”. Kinesthetic learners are defined as people who learn through hands-on experiences and prefer to move and stay active as they are learning. The other common types of learning are “visual” and “auditory”, i.e. people that learn primarily from seeing and observing, and people that learn from hearing and listening. Manufacturing is a natural draw for people that like to work with, and on, tactile things and be able to see the results of their efforts as physical, tangible outcomes. We often hear pitches for the trades suggesting that “not everyone wants to be a doctor, lawyer or teacher”, and that’s true. Although the outputs from those careers are rewarding for many, and for society, they are not “tactile” and not as rewarding or satisfying for everyone. Manufacturing provides meaningful and rewarding employment for many, with the rewards being both monetary as well as a sense of satisfaction.

The second big reason I love manufacturing is its impact on society. In my opinion, manufacturing is what initially created and now sustains our middle class. I’m not an economics major, but here’s my layperson’s explanation of how manufacturing creates wealth for the masses of individuals, rather than just for the few, or for governments or nations that control resources. Manufacturing is a “secondary” industry. Forestry, mining, agriculture, etc. are “primary” industries. The value of material harvested from a primary industry is directly (solely) related to the value of that raw, unprocessed commodity. There is not much income to be generated for the masses, other than through the harvesting and sale process. As a “secondary” industry, manufacturing adds value to the raw material by shaping it, assembling it, refining it; in other words, turning it in to something of far greater value. From a few quick google searches, the cost of the raw materials (materials from primary industries) of a car is estimated to be $2,000. The average price of a car produced in North America last year (2022) was $48,000 (Cdn). This means that something that had only $2,000 of value was turned into something that had $48,000 of value, and that increase in value was primarily due to the value added in all the various direct and indirect manufacturing processes. Yes, machines do a lot of the work, but the machines, and all the tooling for the machines, have to be manufactured. And today, anything that is manufactured in any kind of volume, has to be engineered. People are involved “adding value” up and down the chain, creating not just products, but economic wealth for individuals, companies, communities, and entire regions. Now multiply that $2,000-to-$48,000 value adding factor by 2.5 million, because that’s how many cars are produced in North America each year, and its easy to see why manufacturing is critical to our society’s economic well-being.

The third reason I love manufacturing is attitude. There is very little grey area in manufacturing; its done, or its not. It’s on time, or its not. They don’t expect others to fix their problems, they just naturally set out to fix it themselves. They succeed or they fail, and the outcome is entirely on them; they got it done, or they didn’t. They answer to the consumers every step of the way. Does their product sell? If not, they didn’t design the right product, so they design something new. Does the product work? If not, they fix it under warranty, or they risk losing a repeat customer – and manufacturers know their survival relies on being able to sell to those same customers again. In rare occurrences, some manufacturers have looked to governments for assistance and sometimes for incentives to invest more in the region, but I’d argue that is more the consequence of unbalanced international social and economic policies that disadvantage companies that do most of the “value adding” (i.e. manufacturing) activity here. Although consumers are the ultimate judge of a manufacturer’s success, government policy has a large impact on whether or not the “value adding” (i.e. personal wealth creation) activities can be done here.

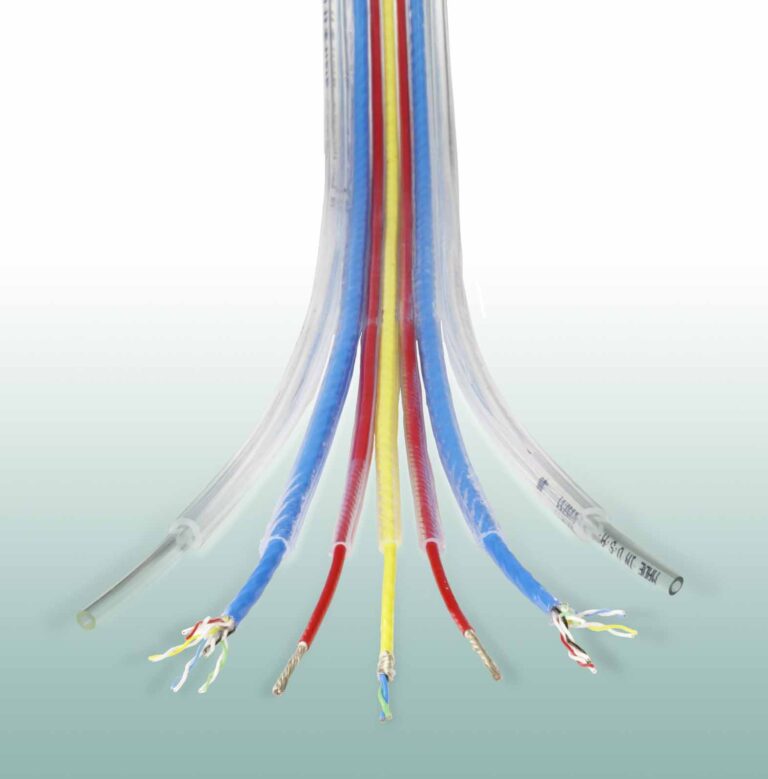

The fourth reason I love manufacturers is they are inventive; they create products that we use and enjoy daily, and often take for granted. And, they find ways to do it in a way that most of us can afford. At one time, automobiles were just for the ultra rich, but Henry Ford and Ferdinand Porsche changed all that. They both went against the grain and designed cars that were intended to be sold to the average person, but Henry Ford also created the processes to actually build them at an affordable cost. The same need for inventiveness applies to every manufacturer today; it is up to them to have the right product to produce that their customers will purchase, and up to them to figure out a way to produce it (hopefully here) at a competitive yet profitable price. They rely on their inventiveness as their primary tool to solve the challenges they encounter. Although some will say that some manufacturers are slow to change, I’d argue that they change and adapt far faster than other major sectors like education and healthcare; manufacturing relies first on their inherent and innate inventiveness rather that having to react to policies that may take years, sometimes decades, to change.

Manufacturing delivers, day in and day out. It makes the products we love, at prices we can afford, while at the same time providing meaningful and rewarding jobs, generating sustainable income for tens of thousands of families. How could we not love our manufacturing sector?